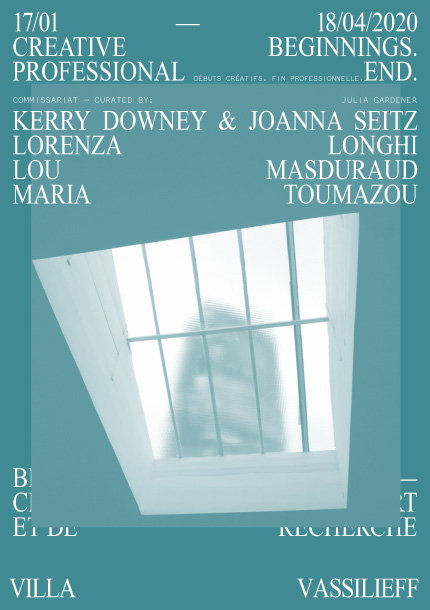

Creative Beginnings. Professional End.

Kerry Downey & Joanna Seitz, Lou Masduraud,

Lorenza Longhi and Maria Toumazou.

Exhibition from 01.17 to 04.18.2020

Curated by Julia Gardener

- Flyer of the exhibition Creative Beginnings. Professional End.

Villa Vassilieff hosts a group exhibition centred around the Tour Maine-Montparnasse as an emblem of ‘site’. Tour Maine-Montparnasse is located just 750 meters away from Villa Vassilieff. The 1970s skyscraper – the first and, for a long-time after, the only one in Paris – remains universally and passionately detested in the city. The joke goes that the towering office block has the best views because you can’t see the tower itself. Positioned in the neighbourhood the building’s towering presence stands for the effects of gentrification, modernization, and globalization on space. This exhibition investigates the threatened specificity of local sites as opposed to universalizing structures, bringing together art practices that center practical, mass produced, and patented objects within interrogated commercial spaces.

Creative Beginnings. Professional End. - by Julia Gardener

There is an irony to working on an exhibition that centres on one skyscraper in Paris when I am curating most of it from New York– a soaring urban centre and home to over 7,000 high-rise buildings. “Le petit Manhattan de Montparnasse”, as seen from Manhattan proper.

A skyscraper is generally understood as a very tall building. Architecturally, it is classified as a building of specific height and support. It is also the building that King Kong climbs in every

There is an irony to working on an exhibition that centres on one skyscraper in Paris when I am curating most of it from New York – a soaring urban centre and home to over 7,000 high-rise buildings. “Le petit Manhattan de Montparnasse”, as seen from Manhattan proper.

A skyscraper is generally understood as a very tall building. Architecturally, it is classified as a building of specific height and support. It is also the building that King Kong climbs in every iteration of the eponymous movie. In 1964, it’s the sole subject of Andy Warhol’s eight hour film, Empire. And in 2002, it serves as the setting for Matthew Barney’s seminal film, Cremaster 3. Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column – both as two-metre oak sculpture in 1918 and a public steel work in 1937 in Târgu Jiu (Romania) – mimics the building’s shape and promise of infinite height. And as early as 1908, Antoni Gaudí proposed a 360 meter high hotel called Hotel Attraction – meant for the same site that later saw the erection of the Twin Towers, arguably the most consequential skyscrapers of our time.

A skyscraper holds immense symbolic value. As a potentially endless structure, the skyscraper’s soaring height very literally brings us closer to the sky – which, to some, is also closer to heaven. Often likened to temples and palaces of the past, the skyscraper symbolizes economic wealth, progress, and power. Yet, the Italian architect and theorist Manfredo Tafuri accurately noted that the skyscraper is both the instrument and expression of capitalism. And capitalism’s force on space is always shadowed by gentrification, modernization, and globalization.

A skyscraper in Montparnasse was a uniquely unsuccessful project, spurring a ban on similar structures in the city for decades in Paris. Tour Montparnasse quickly attracted severe backlash on aesthetic, practical, and local grounds. The city’s grand plan of creating a moneymaking apex turned the neighbourhood into an organizational nightmare – lacking in logical spatial organization and green space, and unable to inscribe itself into the wider urban context. In a 2008 poll of editors on Virtualtourist, the tower’s simple architecture, large proportions, and monolithic appearance won the Tour Montparnasse second place in the awards for the ugliest building in the world. Boston City Hall won first place.

Yet, despite its wide array of criticism, the tower has actually been host to a range of motivations, missions, and mandates. At various times, it has housed the Qatari news channel Al Jazeera, the cooperative financial institution Crédit Agricole, the Dutch multinational electronics conglomerate Philips, the French National Architects Council, and the paradigm of gig economy– co-working space. The national lottery was shot there in the 80s and 90s, and two presidents – François Mitterrand and Emmanuel Macron – headquartered their campaigns in the building’s offices.

There is an irony to considering a skyscraper from an institution whose mission is to uphold an area’s rich, artist driven past. Just 750 meters away from the tower, Villa Vassilieff’s quarters have a longstanding history of artistic activity. Starting as an atelier in the early 1900s, the building has acted as a canteen for artists, a gallery and a museum [2] before it becomes a space for residencies, research, and exhibitions. From this setting, the tension between Tour Montparnasse’s fraught history and its impending future – the recently announced 300 million-euro refurbishment scheduled in time for the 2024 Olympic Games — provides particularly fertile ground for artistic work.

This exhibition takes is name – Creative beginnings. Professional End. – from an Airbnb guide about the neighbourhood. It brings together a video by Kerry Downey and Joanna Seitz, adapted work by Maria Toumazou, and new commissions by Lorenza Longhi and Lou Masduraud. The Tour Montparnasse operates as an emblem of ‘site’– but one that is perceived from a distance and only as one version of a broader typology. Through their own lens and locations, every artist contemplates threatened specificity and identity in a friction against universalizing structures.

Downey and Seitz’s video explores the office as a site that has a symbiotic relationship with the body. Jen Rosenblit’s filmed performance interacts with the architecture and the objects within it to reveal a rowdy, riotous, and resolute resistance against the stifling forces of professionalized space. Next to this, Toumazou’s sculptures take the physical residue of corporate culture to materially blend capitalist, consumerist aesthetics with local, lyrical forms. Through laborious and artisanal processes, her work investigates how homogenous structures push up against distinct locality.Inhabiting zones of passage across both floors, Longhi’s interventions complicate the experience of moving through space. Her screen-prints and neons rely on reproduction to refer to specific elements of the space of display at Villa Vassilieff or the space of reference at Tour Montparnasse. Moving along the walls, Masduraud’s rhizomatic design snakes its way from the reception, where work is perpetually visible, to the institution’s office, where work is habitually invisible, to bind together the all-consuming modes of contemporary labour. The in-situ installation employs discarded drawers and a long wax skeleton, gutting out an anatomical and constructural support system before putting both on shared display.

Together, the artists in Creative beginnings. Professional End. explore their specific investments into gentrification, modernization, and globalization through a distinct, but universal, symbol.If you look out the window here in Paris, you can see the Tour Montparnasse – but if you are in New York, or in Nicosia, or in Milan, or in Geneva, you are likely to see another soaring skyscraper not unlike this one. Maybe across the sky – across all the languages and the climates and the time zones – all the skyscrapers share some horizontal plane above the clouds, seeing eye to eye above us all. But then let us stay here, low on the ground – bound to the languages and the climates and the time zones – to collectively contemplate their promise, their illusion, and their might.

Julia Gardener is from Warsaw, Poland and grew up between her hometown, and London, UK. Currently, she is a graduate student at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, New York, where she is working towards her thesis. Her research focuses on site-oriented practices with special attention to the influences of late capitalism on space and place, as well as its impact on their specificity. Prior to CCS, Gardener studied English Literature at the University of Bristol, going on to work in cultural journalism and in commercial and non-profit gallery spaces. From 2016 to 2017, she was the gallery and communications manager at the nomadic exhibition programme Emalin, and aided in opening a permanent gallery space alongside the directors in London, UK. In this position, she worked primarily with emerging artists towards exhibitions and international art fairs. In 2017, Gardener co-founded Hot Wheels Projects – now Hot Wheels Athens – with Hugo Wheeler in Athens, Greece. The curatorially driven space produces exhibitions, events, and publications with both local and international artists. In 2019, she was a curatorial fellow at Bétonsalon in Paris, France.

[1] In this space, Marie Vassilieff had her studio at the beginning of the century, and then opened an academy and a canteen for neighbouring artists who were facing hard living conditions during World War I. In 1972, the Atelier Annick Le Moine opened on Villa Vassilieff’s current first floor. This gallery organized numerous exhibitions, concerts, and performances. After Annick Le Moine’s death in 1987, Charles Sablon took over the former space to open his own gallery, which he ran until he passed away in 1993. In 1998, the Musée du Montparnasse non-profit organization created by Roger Pic and Jean‑Marie Drot took over the space until 2013.

[2] In this space, Marie Vassilieff had her studio at the beginning of the century, and then opened an academy and a canteen for neighbouring artists who were facing hard living conditions during World War I. In 1972, the Atelier Annick Le Moine opened on Villa Vassilieff’s current first floor. This gallery organized numerous exhibitions, concerts, and performances. After Annick Le Moine’s death in 1987, Charles Sablon took over the former space to open his own gallery, which he ran until he passed away in 1993. In 1998, the Musée du Montparnasse non-profit organization created by Roger Pic and Jean‑Marie Drot took over the space until 2013.

Partager