I, the Archive - Euridice Zaituna Kala

Ending - From December 15 to 20, the exhibition I, the Archive by Euridice Zaituna Kala will be open to the public for one last time before its dismantling. We hope to meet many of you to discover or rediscover her work, and are happy to welcome you during this week, which will unfortunately mark the conclusion of the project carried out by Bétonsalon – Center for Art and Research at the Villa Vassilieff, which will close its doors definitively after the closing of the exhibition.

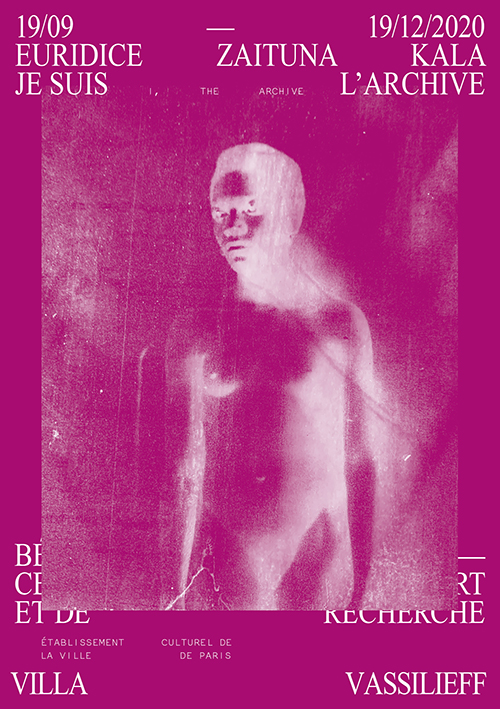

- Euridice Zaituna Kala, I, the archive, Villa Vassilieff, 2020.

Exhibition from 09.19 to 12.20.2020

On a proposal by Mélanie Bouteloup

Curated by Camille Chenais

In September 2020, the artist Euridice Zaituna Kala takes over the space of the Villa Vassilieff with the exhibition I, the Archive, presenting a narrative and sensitive re-reading of the Marc Vaux archive, on which the artist worked as part of the ADAGP - Villa Vassilieff grant. Through a mental and audio journey, the exhibition mixes the artist’s own memories and references with reflections on the archives themselves, their fragility, their porosity, and their lacks. By including singular individualities in these archives, Euridice Zaituna Kala reclaims the writing of history and shows, through the interweaving of these destinies, that another shared and collective history is possible.

Euridice Zaituna Kala’s project I, The Archive is supported by the ADAGP - Villa Vassilieff scholarship, in partnership with the Kandinsky Library, MNAM-CCI, Centre-Pompidou.

Actor·actresses : Salomon Mbala Metila, Lou Justine Moua Nedellec, Louna Philip ; Sound engineer : Marion Leyrahoux ; Seamstress : Carla Magnier ; Recording studio : Time-Line Factory, Valentin Gueriot ; Handler : Romain Grateau

I, the Archive

“What happens if the histories you want to know have left no records? ”

Euridice Zaituna Kala is the archive. The archive is enmeshed in the pores of her skin, the folds of her memory and her recollections of meetings, texts and journeys. Invited by the ADAGP (Association for the Development of the Graphic and Visual Arts), Villa Vassilieff and Bibliothèque Kandinsky to work with the Marc Vaux collection, Euridice Zaituna Kala has herself become the archive. Euridice has enthusiastically taken on this new role by searching for familiar figures from her memories and personal set of references: Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, her father Getulio Mario Kala... By becoming the archive, Euridice gathers, sorts and interprets information according to its affective value rather than its historical relevance. Becoming the archive means reclaiming power by writing history free of institutional norms. It means shedding light on people and geographical areas who have been deliberately excluded from historical accounts and giving visibility to groups of people who have been forgotten by hegemonic narratives. “I became this other power that was going to foreground whatever I wanted and however I wanted to portray it, regardless of how it has been established in existing archives.” By approaching the archive through her individual subjectivity and focusing on people she is intimately connected to, the artist attempts to develop a plural, personal and deviant manner of recounting history.

As Euridice browsed the Marc Vaux collection, certain photographs caught her eye: a portrait of the Black model Aïcha Goblet, sketches of Josephine Baker by Jean de Botton and two portraits of unknown nude Black models. The artist was drawn to these familiar bodies which resembled her own. Euridice reflected on these bodies’ presence in these photographs and their absence from the archives from which monolithic narratives of modern art have been constructed. Rather than reproducing these photographs in her exhibition, the artist instead chose to use narration to draw attention to the bodies frozen and framed in these images – trapped by the projections and fantasies of others.

Euridice Zaituna Kala is also interested in absent images: those that have gone missing, those never taken by Marc Vaux, those that have never been located. Who misses these missing images? How did they go missing? Do they exist somewhere else other than in the Vaux photographs? The Marc Vaux archives are a mammoth collection. They contain more than 127,000 photographs and feature more than 5,000 listed artists and 11,000 boxes of glass plate negatives. Usually praised for their breadth and comprehensiveness, Euridice demonstrates that, like any archive, the Vaux collection is defined by its creator’s subjectivity and material constraints. Figures like Ernest Mancoba, Gerard Sekoto, James Baldwin and Katherine Dunham do not feature in the collection. “There are no missing images unless someone is missing them.” Someone must miss these images for their absence to be noticed. History sorts between the remembered and the forgotten. “In Paris”, Euridice told me, “images were sorted by erasing Black bodies. Now, I have a utopian dream of redressing this imbalance by putting these bodies back into the archive that erased them.”

Paul Veyne described history as “patchwork knowledge” or “mutilated knowledge” due to the scarcity of archives and sources. Yet, history often states, delimits and orders things or sets facts in stone. Here, instead, Kala chooses to ground her exhibition in doubt, uncertainty and interpretation. Absence becomes tangible, visible and audible. Absence also becomes fiction. Voices guide visitors as they walk through the exhibition. This sound piece, written by Euridice Zaituna Kala, blends references to Marc Vaux’s photographs and other photographs with mentions of Black historical figures who spent time in Paris and autofiction based on her own experiences as a Black, Mozambican, African and migrant woman. The piece is a sensorial narrative inspired by Léopold Sédar Senghor’s Royaume d’enfance (Kingdom of Childhood). Senghor used this image to describe his attempts to recreate the lost paradise of his childhood in his poetry by rediscovering the power of a child’s imagination. Fiction fills the gaps in archives and joins the dots between partial historical records. “Poetry can extend the document.” Bodiless narrators give a voice to Marc Vaux’s voiceless images, whispering a story that blends different periods, characters and continents. The narrative mixes Mozambique and Paris; the artist’s family history with Marc Vaux’s family history; and the past with the present. It reflects on the difficulty of accessing archives and the challenges of appropriating them.

- Exhibition view, I, the Archive, Euridice Zaituna Kala, Villa Vassilieff, 2020. © ADAGP, Paris, 2020. Photo : Aurélien Mole.

The voices in the exhibition are accompanied by sculptures and visual forms. The space is bathed in coloured lights. One particular material – glass – is particularly prominent in the exhibition space. Euridice Zaituna Kala’s glasswork allows her to develop an quasi-physical connection with Vaux’s archive, by reusing the material the photographer used to create the images in his collection: the negatives from Marc Vaux’s view camera are mounted on glass plates. Euridice has engraved and drawn her own images and memories on rectangular pieces of glass that resemble those from the archive, as if adding to Vaux’s collection by reinserting bodies that were excluded from it. However, the artist chooses to work on the glass with materials that fade over time or disappear, highlighting the fragility of our archives and the precariousness of our attempts to record our histories. Glass, as a material, exemplifies this fragility: how many negatives must have been lost by falling or through other accidents?

Elsewhere in the exhibition space, Euridice’s glass silhouettes subtly recall the nude Black bodies in the archive. These bodies include a model shot by Vaux, a child immortalised by Ricardo Rangel and a male figure sculpted by Max Le Verrier and photographed by Vaux. Euridice makes these people whose names have been lost present in the space but does not expose them to the viewer. Their transparent silhouettes make the shapes of their bodies difficult to discern – as if they were present in negative. The artist uses these sculptures to question how Black bodies have been appropriated by various forms of representation. How can we rewrite the history of bodies when their images only persist through the gaze of the other? How can we once again give these bodies control of their own representation and return to them the privacy that photography has stripped them of? Rather than reappropriating their histories, Euridice affirms their existence. Further on in the space, the artist cuts up silhouettes of Josephine Baker’s banana belt and the profile of Black model Aïcha Goblet in mirror aluminium panels. These women who embodied Western fantasies become mirrors showing visitors their own reflections, symbolising the projections and expectations that have been imposed on these bodies since the 1920s.

Euridice often told me that she imagined this exhibition as a dance with Marc Vaux, in which each partner takes turns at guiding the other. This dance takes place in a permeable space where the archives and the artist mutually influence one another. The artist is shaped by the photographs from the archive she questions in her work. The archive is altered by the gaze of the artist and in turn shapes the perceptions of visitors. Gazes leave a trace on their objects. Patrimony and archives are not sealed and demarcated spaces. They are meant to be questioned, appropriated and reworked. Visitors are, in turn, invited to become the archive – to construct and rewrite their own history. “I am the archive; you are the archive.”

Camille Chenais

Translation from French: Michael Angland

-

Je suis l’archive, Euridice Zaituna Kala (Vimeo - 167 bytes)

Partager